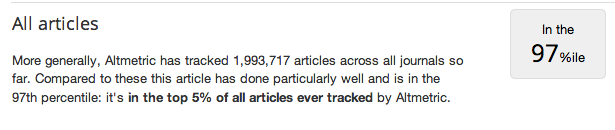

A few months ago, I mentioned how academia.edu provides near-real-time tracking of visits and visitor demographics for any publications and used my own paper “Are We All Online Content Creators Now? Web 2.0 and Digital Divides” as an example to show how it works. Recently I came across a new tool that makes this tracking process much easier – Altmetric is an academic-focused social media tracking company. It makes its money selling large-scale data to publishers and academic institutions but if you are an academic and you have published anything with a DOI (or you want to find out something about the social media footprint of a competitor’s work for that matter) then Altmetric can display a “dashboard” of data like this. I’m quite pleased about this particular metric:

Archive for the 'publishing' Category | back to home

Just as the old year passes I have finished off the last substantive chapter to my upcoming book. Now all I have to do is:

- Add a concluding chapter

- Go through and fill in all the [some more clever stuff here] bits

- Check the structure and ensure I haven’t repeated myself too often

- Incorporate comments from my academic colleagues and friends

- Submit to publisher

- Incorporate comments from my editor and their reviewers

- Index everything

- Deal with inevitable proofing fiddly bits

- Pace for months while physical printing processes happen… then…

- I Haz Book!

Doesn’t seem like too much further, does it?

Update Jan 2, 2014 – I have finished my draft concluding chapter, which ends, “[some form of ringing final summing-up here!]”

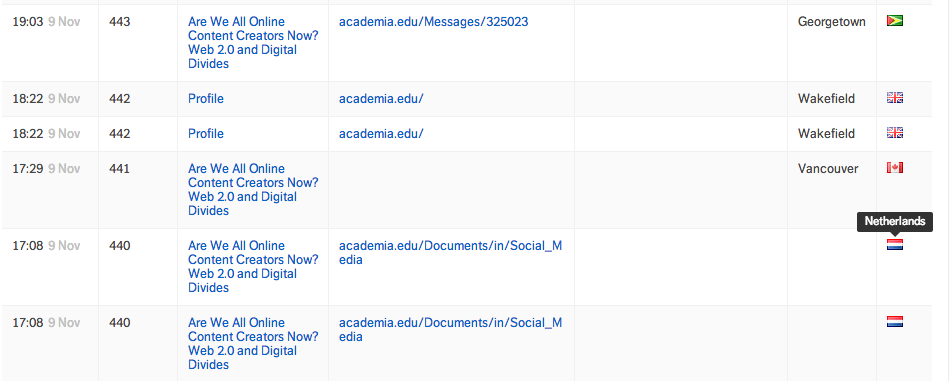

Just as we are all finding out how much the government has been tracking our meta-data, a whole ecosystem of public-facing meta-data tracking services is arising, giving us the chance to measure our own activity and track the diffusion of our messages across the web. This is particularly noticeable when looking at Twitter but other social media also increasingly offer sophisticated analytics tools.

Thus it was that as my latest open access paper “Are We All Online Content Creators Now? Web 2.0 and Digital Divides” went live two days ago I found myself not just mentioning it to colleagues but feeling obliged to update multiple profiles and services across the web – Facebook, Twitter, academia.edu, Mendeley and Linkedin. I found to my surprise that (by tracking my announcetweet using Buffer) only 1% of the thousands I have ‘reached’ so far seem to have checked my abstract. On the other hand, my academia.edu announcement has brought me twice as many readers. More proof that it’s not how many but what kind of followers you have that matters most.

Pleasingly, from Academia.edu I can also see that my paper has already been read in Canada, the US, Guyana, South Africa, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, and of course the UK.

The biggest surprise? Google can find my paper already on academia.edu but has not yet indexed the original journal page!

I will share more data as I get it if my fellow scholars are interested. Anyone else have any data to share?

One of the chapters of my forthcoming book, “Sharing Our Lives Online: Risks and Exposure in Social Media” is devoted to the question “What is risky and who is at risk?” and in answering this question the best resource I have consulted by some distance is Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Gorzig, A., & Olafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the internet: the perspective of European children: full findings. It combines the findings of a survey of 25,142 (!) children 9-16 across Europe with a measured, thoughtful review of the research of others. Parents and policy-makers who don’t want or need all the 167 pages of evidence should download EU Kids Online: Final Report and pay particular attention to pages 42-46 which debunk the top 10 myths of online safety and set out some clear recommendations. Here are a few things I have noted, based on my interests and approach:

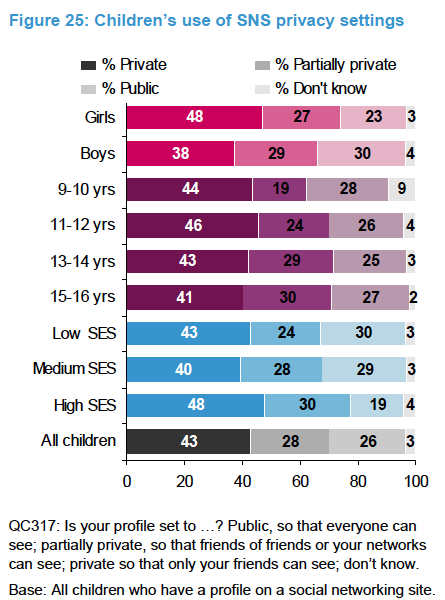

The survey found that 59% of all European children surveyed have social network profiles, including 26% of 9-10 year olds and 49% of 11-12 year olds (though a proportion of these will be on social networks where under-13s are allowed like Club Penguin). (p. 36-37)

The survey looked at children’s use of privacy settings but (presumably because of lack of space on the very extensive survey) in a fairly blunt fashion. It asked them whether their profiles were public, “partly private” (visible to friends of friends) or private. How concerned you are about what they reveal may depend on how you perceive “partly private”.

Research published by scholars working with Facebook (Ugander et al, 2011) noted that “partially private” users with the average number of friends (100) would have on average 27,500 friends of friends able to view their profiles.

This research also does not evaluate how accurate the respondents’ assessments really are of how well their profiles are protected. The only study I am aware of that compared what people wanted to share on Facebook with what they were actually sharing (Majedski, 2011) found no fewer than 93.8% of participants revealed some information that they did not want disclosed. This is consistent with the earlier qualitative findings of (Livingstone, 2008) who found on interviewing teenagers, “When asked, a fair proportion of those interviewed hesitated to show how to change their privacy settings, often clicking on the wrong options before managing this task, and showing some nervousness about the unintended consequences of changing settings” (p. 406).

On the other hand, the survey does not give much guidance about just how risky letting out public information actually is for young people. They say, “Research thus far has proved contradictory about whether SNSs are more or less risky than instant messaging, chat, or other online communication formats, and it is as yet unclear whether risks are ‘migrating’ from older formats to SNSs” (p. 36) but their list of risks is rather vague – ‘flaming’, hacking and harassment – and the only paper they cite about these risks is (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2008) whose scope just covers harassment and sexual solicitation and which seemed rather more unambiguous than the EU Kids Online report suggests. It concluded “broad claims of victimization risk, at least defined as unwanted sexual solicitation or harassment, associated with social networking sites do not seem justified” – though the situation may have changed in the six years since the Ybarra & Mitchell survey.

It is perhaps notable that while online bullying was found to be rare – 6% of young people experienced it in the last year (p. 63) – it is also most often encountered on social network sites (half of all bullying encounters).

It’s unfortunate that the focus of the report (on “the internet”) means it doesn’t cover mobile-phone based risks unless they came via the internet (bullying, ‘sexting’ and other problematic behaviour may be digitally circulated on mobiles but not using the internet).

My biggest problem with the report, however (and one of my motivations to do my book) is that the definition of potential risks in the survey is too narrow. In focusing on the obvious short term issues it overlooks some of the longer term risks of internet use including but not limited to:

- Employment harm (“why were you drunk all the time at university?”)

- Relationship harms (when your grandmother ‘meets’ your girlfriend online)

- Harms from an unanticipated future (“I can’t believe you actually boasted about having a petrol-guzzling car back in the 90s”)

- identity theft

- Locational crime (you check in at the restaurant, a thief checks out your TV)

- The harvesting of personal data for targeted marketing (and possibly ‘redlining’ and exclusion from access to financial products)

- Government surveillance using (flawed) risk assessment criteria (one of your 22,000 friends of friends turns out to be a terrorist so you go on a watch list).

I may share more about research I run across that tackles some of these areas in future blog posts. Meanwhile, I would be interested in what you think of this post and (if you’re a researcher) please suggest studies you think do a good job of measuring problems 1-7.

Oh, and perhaps my biggest problem with this report (but one the authors can hardly be blamed f0r) – in common with most internet risk literature it studies only children and teenagers. I would like to redress the balance by noting that many of the problems above will be encountered by adults as well. (So studies about these risks that cover older people would be particularly welcome).

A recent discussion about e-book sales among “indie” authors (those who have not been published traditionally or with minimal experience of conventional publishing) has inspired some interesting number crunching and (it seems to me) some rather overoptimistic speculation about the prospects for new authors who attempt to bypass the publisher system altogether by doing their own publicity and publishing electronically.

One of the most vociferous proponents of the “go it alone” model for authorship is thriller writer Joe Konrath, but critics of his approach often say that his success with self publishing could be due in large part to his already having been a conventionally published author before moving aggressively into online sales. Robin Sullivan, a guest on his blog, unveiled an analysis of 54 ‘indie’ authors who revealed on an electronic publishing message board that they were selling more than 1000 books a month. On top of that list is Amanda Hocking, who claims to have sold more than 450,000 titles in January alone.

Robin, who is the publicist for (and wife of) Michael Sullivan, an author on that list, provides some more detailed information about the economics of being an author of this kind in her posting. Derek Canyon also discusses the economics and provides a breakdown of the authors on that list by genre and by number of books in “print”.

It is undeniably true that, as Robin and Joe claim, it is possible to “do well” self publishing without having been published already conventionally- only six of the 54 authors on their list had been published by major publishers, for example. Nonetheless, some caution is in order. A few concerns leap out at me:

- This is a self-selecting sample out of an unknown population providing self reported statistics. Leaving aside the question of whether they have an interest in exaggerating their sales, this gives us no information about how easy it might be for others to follow their leads.

- no information is provided about the balance of sales between e-books and regular books (although given the source is kindleboards.com one can imagine that the proportion of e-book sales would be high), and more importantly we do not know the price at which each book is sold. This is important because it is possible to sell one’s book on Kindle for as little as $.99 (and if you do you only get $0.30 per book sold).

- The implicit definition of “doing well” as an independent author is, it seems to me, a rather undemanding one. As Derek Canyon puts it:

- If you look at the list of primary genres for the authors who are included in this self-selecting survey, it does not include literary fiction or poetry. Whether this is because “literary” authors do not hang out on this particular bulletin board, because such authors are not interested in ebooks, because literary fiction or poetry have a hard time selling as e-books or simply because they always have a hard time selling in the market as a whole compared to “genre” works is unclear.

If you assume that the cover price of the book is $2.99 (the minimum required to receive a 70% royalty from Amazon), then the author is making just over $2,000 per month, or $24,000 per year!

Median income of workers in the US in 2009 was $36,000 for men, $26,000 for women – for graduates (and I am guessing most writers are), this rises to $62k or $44k. If earning $24k a year is success, then “don’t give up your day job” (and many writers don’t). Mind you, things look a lot better if you compare only to other writers. A survey of UK writers in 2005 found that even those who spent more than 50% of their time writing, earned 64% of the median wage.

Clearly it is very early days in the development of electronic publishing and e-books. It remains very possible that bypassing conventional publishing to market and sell e-books will indeed become a viable option for many authors or even, potentially, a dominant one as e-book reader technology continues to develop and as the devices become increasingly popular. I think that individual case studies and small-scale surveys like these can provide an interesting snapshot of the current state of development, but I also think it is a mistake to read too much into them.

I hope in the coming years to be able to shed more light on this fascinating subject myself – stay tuned!

1) I started my new job as Senior Lecturer in the Division of Journalism and Communication at the University of Bedfordshire this week and have enjoyed meeting my new colleagues (and collecting my new Macbook Pro).

2) I just met my editor at Palgrave and agreed to write a book (my first full-length academic one) provisionally titled “Sharing Our Lives Online: Risks and Exposure in Social Media” – likely to be delivered in 2013. I plan to blog about it as I write using the “Sharing Our Lives Online” category, so keep an eye on that…

3) On my way back from that meeting I discovered that my wife has also just found a position for when her current one finishes, which given the turbulent situation in the NHS where she works is a big relief.

Of course I would be open to receiving further good news but these three bits of news are certainly enough to be starting with!