One of the chapters of my forthcoming book, “Sharing Our Lives Online: Risks and Exposure in Social Media” is devoted to the question “What is risky and who is at risk?” and in answering this question the best resource I have consulted by some distance is Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Gorzig, A., & Olafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the internet: the perspective of European children: full findings. It combines the findings of a survey of 25,142 (!) children 9-16 across Europe with a measured, thoughtful review of the research of others. Parents and policy-makers who don’t want or need all the 167 pages of evidence should download EU Kids Online: Final Report and pay particular attention to pages 42-46 which debunk the top 10 myths of online safety and set out some clear recommendations. Here are a few things I have noted, based on my interests and approach:

The survey found that 59% of all European children surveyed have social network profiles, including 26% of 9-10 year olds and 49% of 11-12 year olds (though a proportion of these will be on social networks where under-13s are allowed like Club Penguin). (p. 36-37)

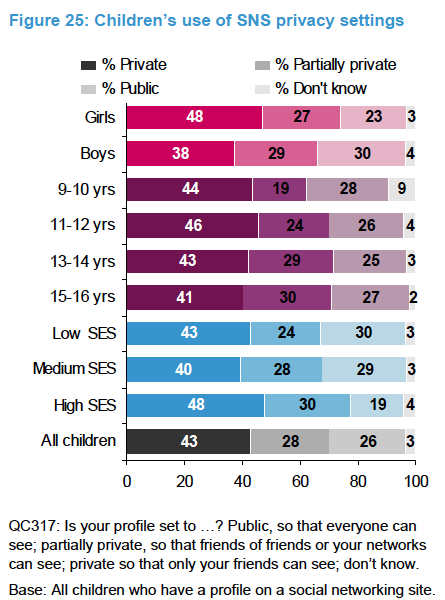

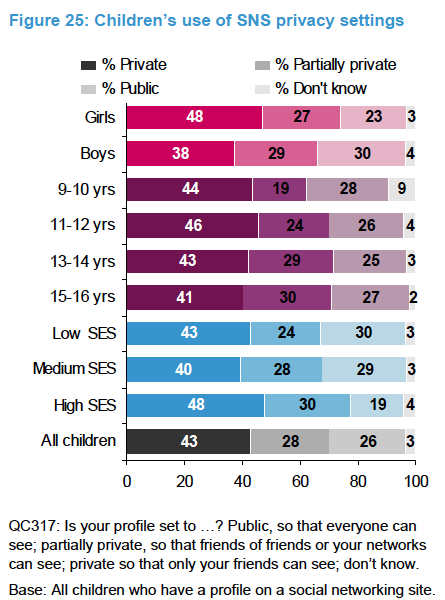

The survey looked at children’s use of privacy settings but (presumably because of lack of space on the very extensive survey) in a fairly blunt fashion. It asked them whether their profiles were public, “partly private” (visible to friends of friends) or private. How concerned you are about what they reveal may depend on how you perceive “partly private”.

From Risks and Safety on the Internet p. 38

Research published by scholars working with Facebook (Ugander et al, 2011) noted that “partially private” users with the average number of friends (100) would have on average 27,500 friends of friends able to view their profiles.

This research also does not evaluate how accurate the respondents’ assessments really are of how well their profiles are protected. The only study I am aware of that compared what people wanted to share on Facebook with what they were actually sharing (Majedski, 2011) found no fewer than 93.8% of participants revealed some information that they did not want disclosed. This is consistent with the earlier qualitative findings of (Livingstone, 2008) who found on interviewing teenagers, “When asked, a fair proportion of those interviewed hesitated to show how to change their privacy settings, often clicking on the wrong options before managing this task, and showing some nervousness about the unintended consequences of changing settings” (p. 406).

On the other hand, the survey does not give much guidance about just how risky letting out public information actually is for young people. They say, “Research thus far has proved contradictory about whether SNSs are more or less risky than instant messaging, chat, or other online communication formats, and it is as yet unclear whether risks are ‘migrating’ from older formats to SNSs” (p. 36) but their list of risks is rather vague – ‘flaming’, hacking and harassment – and the only paper they cite about these risks is (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2008) whose scope just covers harassment and sexual solicitation and which seemed rather more unambiguous than the EU Kids Online report suggests. It concluded “broad claims of victimization risk, at least defined as unwanted sexual solicitation or harassment, associated with social networking sites do not seem justified” – though the situation may have changed in the six years since the Ybarra & Mitchell survey.

It is perhaps notable that while online bullying was found to be rare – 6% of young people experienced it in the last year (p. 63) – it is also most often encountered on social network sites (half of all bullying encounters).

It’s unfortunate that the focus of the report (on “the internet”) means it doesn’t cover mobile-phone based risks unless they came via the internet (bullying, ‘sexting’ and other problematic behaviour may be digitally circulated on mobiles but not using the internet).

My biggest problem with the report, however (and one of my motivations to do my book) is that the definition of potential risks in the survey is too narrow. In focusing on the obvious short term issues it overlooks some of the longer term risks of internet use including but not limited to:

- Employment harm (“why were you drunk all the time at university?”)

- Relationship harms (when your grandmother ‘meets’ your girlfriend online)

- Harms from an unanticipated future (“I can’t believe you actually boasted about having a petrol-guzzling car back in the 90s”)

- identity theft

- Locational crime (you check in at the restaurant, a thief checks out your TV)

- The harvesting of personal data for targeted marketing (and possibly ‘redlining’ and exclusion from access to financial products)

- Government surveillance using (flawed) risk assessment criteria (one of your 22,000 friends of friends turns out to be a terrorist so you go on a watch list).

I may share more about research I run across that tackles some of these areas in future blog posts. Meanwhile, I would be interested in what you think of this post and (if you’re a researcher) please suggest studies you think do a good job of measuring problems 1-7.

Oh, and perhaps my biggest problem with this report (but one the authors can hardly be blamed f0r) – in common with most internet risk literature it studies only children and teenagers. I would like to redress the balance by noting that many of the problems above will be encountered by adults as well. (So studies about these risks that cover older people would be particularly welcome).