A new paper by Aaron Shaw and one of my favourite scholars, Eszter Hargittai, provides some fascinating insights into why there are inequalities in people’s participation online – in this case in editing Wikipedia. TL;DR a representative survey of the US population shows 3.5% had never heard of Wikipedia, of those who had heard of it, 18.5% said they had never visited (probably an overstatement), and 32% did not know that Wikipedia is editable by anyone – only 8% of those surveyed had ever edited themselves.

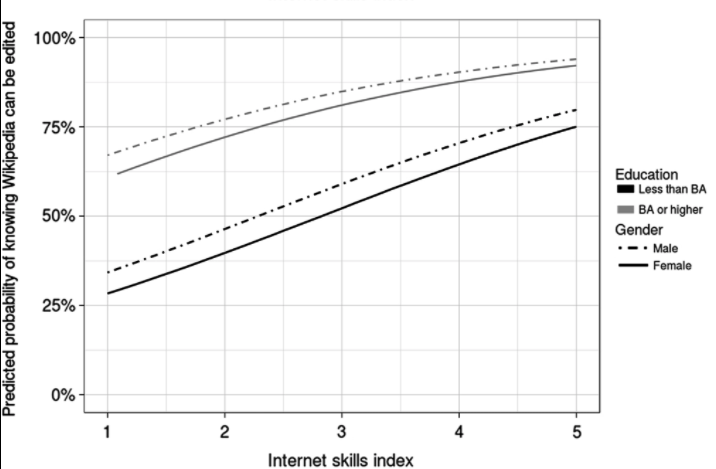

They also found that the likelihood they know Wikipedia is editable varies quite widely depending on user’s overall internet skills but also, importantly, on their overall education level. Even among those who have the highest general internet skills, 25% of those without college degrees didn’t realise they could edit Wikipedia – and among women with low education and low general internet skills only 28% realised they could edit Wikipedia. Imagine how much better Wikipedia could be if the knowledge, interests and experiences of the 92% of non-editors could be mobilised!

What’s not in the paper

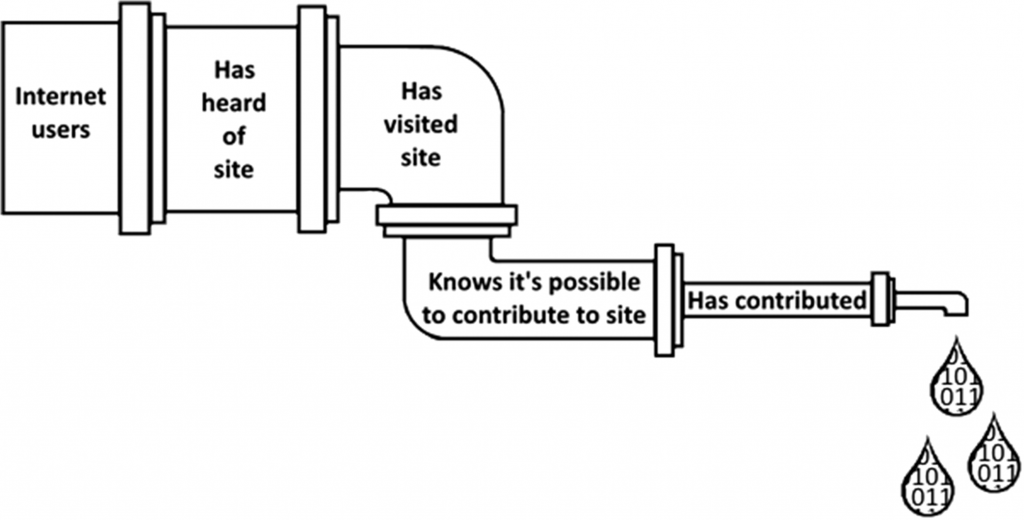

Now, drawing on my own thinking about this area (which I was delighted to see them reference), let’s talk a bit about some of the overarching issues that this paper doesn’t really dig into (no criticism intended here – you can’t cover everything in a single paper!) Here’s the researchers’ conceptual “participation pipeline”:

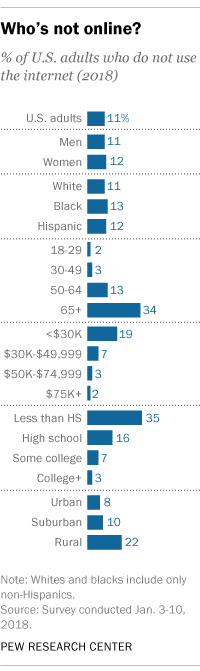

Imagine however that the pipe’s size reflected the actual narrowing at each point (sorry I can’t redraw it but maybe the authors or one of you would like to have a go?). First you would need a section of pipe before “internet users” to show all potential users. In the US, the latest survey data shows 9% of the public still doesn’t use the internet – and a full third of all older people or people with less than a high school education (1).

If you are interested, as I am, in participation on the Internet globally, the pipe would narrow much more sharply and earlier in other parts of the world – over half of the world still isn’t on the internet.

(Source: ITU)

After this, the pipe would narrow a bit by “has heard of” and “has visited” Wikipedia but it would narrow more by “knows it’s possible to edit” (the key finding of this paper). Where the pipe really gets narrow, however, is among those who know they could contribute but don’t (92% of the population).

And what this paper couldn’t really get at is why. We still don’t know enough about this but I suggest a few explanations:

- Ease of access and device type matter – it’s much easier to edit Wikipedia on a computer than on a mobile phone but there are many who access the internet mainly or exclusively on their mobiles.

- Freedom of access matters – not so much an issue in the US but there are many countries where internet use is closely monitored and where writing the ‘wrong thing’ in a Wikipedia entry could get you into serious trouble with your government.

- Internalised power structures. If as a woman, say, or or a poor person or an ethnic minority you are accustomed not to have your voice heard, might you assume nobody wanted to hear it on Wikipedia either (especially if existing Wikipedia articles seemed unsympathetic to your point of view, or if your experience of the editing process was unsympathetic). If you did not have much formal education, you might find it difficult to express yourself in writing and you might be concerned that what you wrote might be scorned or mocked because of spelling or grammatical errors. (For an academic gloss on this, you might want to start with Bourdieu).

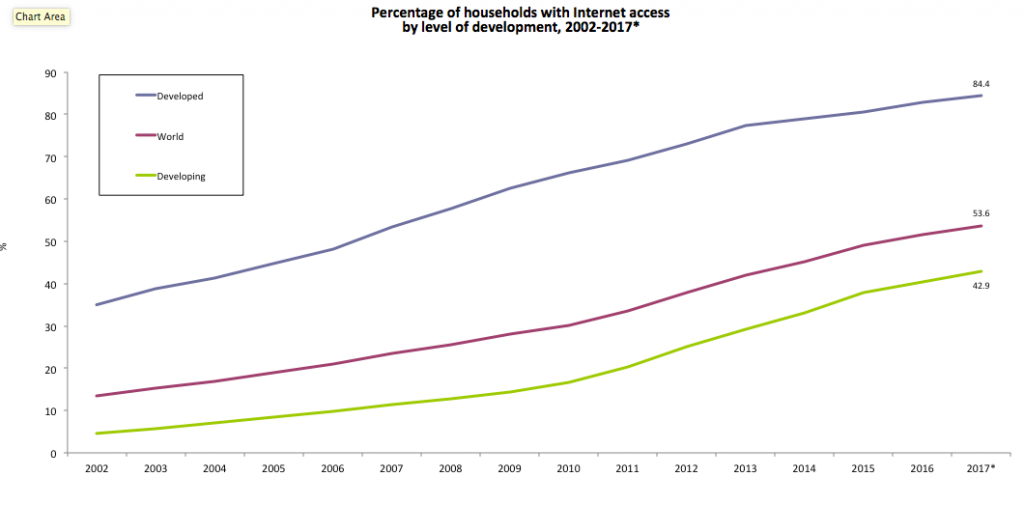

Lastly, there is a further narrowing of the pipe at the end which the authors could (and really should) have taken into consideration – the question of intensity of use. We know from other research that most people who do edit Wikipedia do so infrequently, but most Wikipedia edits overall are made by a tiny number of very active editors:

By Dragons flight – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

By Dragons flight – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

The survey they used would not be able to give statistical information about the backgrounds of those editors but there may be some data about this from Wikipedia’s own surveys and I would be astonished if research did not reveal that most edits made on Wikipedia overall are done by a highly privileged subset of all Wikipedia editors, mainly because of those internalised power structures I mentioned above.

Conclusion

Most of us (and in particular many internet scholars) are accustomed to talk about how ubiquitous and accessible and empowering tools like Wikipedia, weblogs and the like are, but as this research shows it is important to bear in mind how far many potential users are from playing an equal part in online spaces. It’s important to remember how dissimilar internet researchers and pundits are from the whole population – if you are reading this I am guessing you have edited at least one Wikipedia page – I’ve edited about a hundred and I don’t even consider myself an avid Wikipedian. Moreover in looking at the US this research is already looking at the top of the global participation pyramid. We need much more research to highlight the extent of participation gaps globally and action to narrow those gaps.

Footnotes:

- I think that the analysis that this paper did quotes figures for the US population not just for the US online population (even though the survey they did was done online) but if not, you would have to take into account that participation is even more skewed away from the lower-educated (and older) because they are less online in the first place.